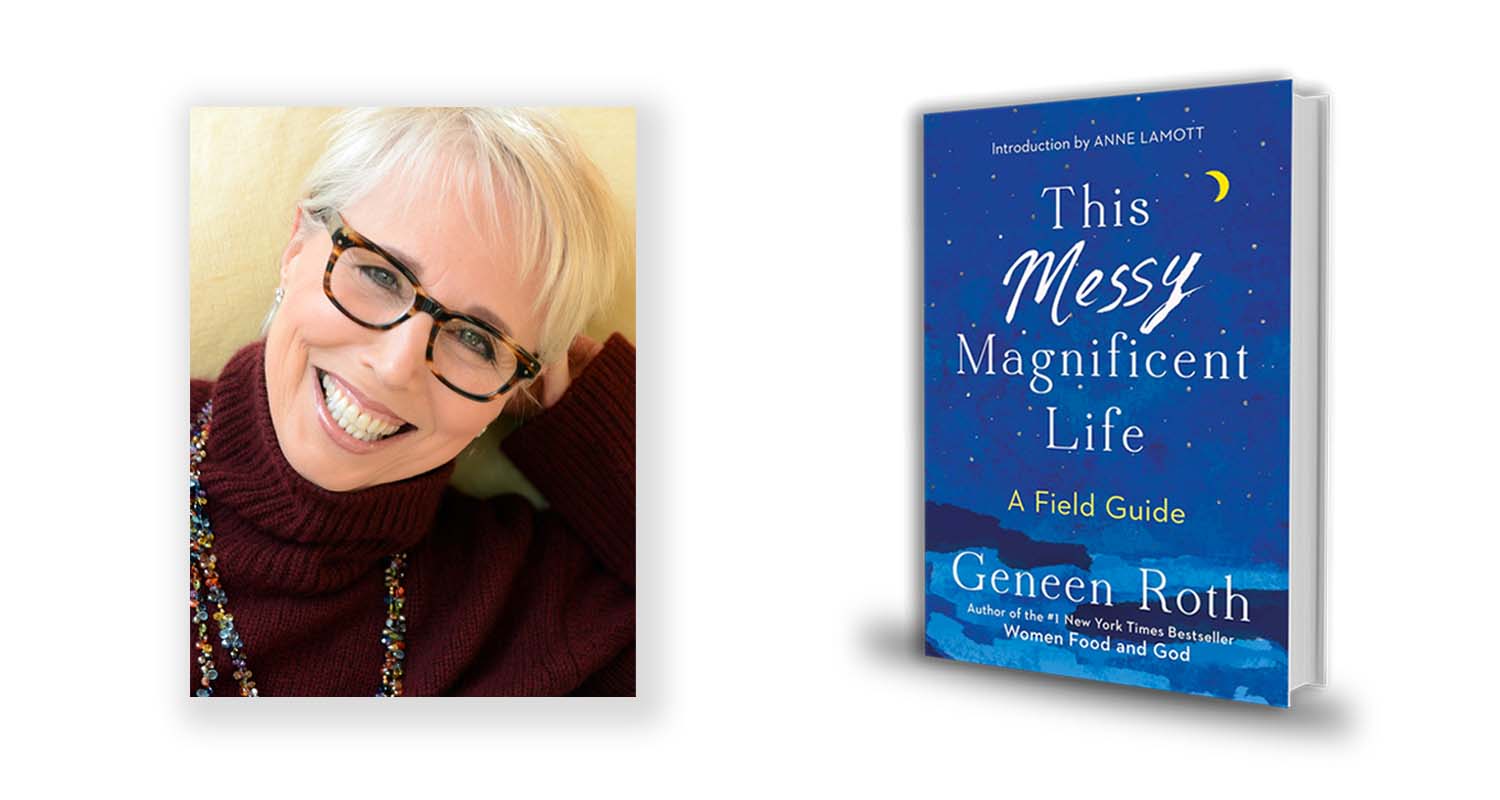

Geneen Roth, author of multiple New York Times bestsellers, has been teaching groundbreaking workshops and retreats for over thirty years about how our eating practices reflect our personal and spiritual issues. She has appeared on numerous national shows including The Oprah Winfrey Show, 20/20, Today, Good Morning America and The View, and today she’s sharing with Bulletproof readers from her new book, This Messy Magnificent Life, about the difficult experiences she had with dieting, and how what she learned from that changed her life.

Two women I know have each had two lap band/gastric sleeve procedures. Not one, but two operations in which they volunteered to have their bodies cut open and risk dying from surgical mistakes — all for weight loss. All four of the operations did exactly what they were supposed to do, and the women did indeed lose weight. But each time, they discovered creative ways to commit sabotage. They ate small amounts, all day long. They ate until they felt as if they would burst. And six months later, the weight started coming back.

The million-dollar answer to the question of why weight loss is so difficult to maintain is that along with the exaltation of being thin, healthy and eating in ways that make you feel more and more alive, come less positive feelings. The lightness that accompanies an unencumbered body feels vulnerable. And if we’ve used our weight in any way, even unconsciously, to keep us safe, the joy of weight loss can be overlaid by a wash of terror.

In my experience, the unspoken reason why many people don’t maintain their weight loss is that they don’t want to be thinner more than they want to stay protected. Or hidden.

In my twenties, a few days from attempting suicide, I realized that I’d been speaking to myself in a language — eating uncontrollably — that I hadn’t bothered to learn or understand. I decided — and this was the most radical and decidedly counterintuitive part — that I would trust the longing at the root of the compulsion rather than believing I was a self-destructive maniac. And once I took that leap and began trusting myself with food — my friends looked at me in horror when I ate whatever I wanted those first few weeks — everything changed.

The ongoing question was no longer what I could do to control my insanity, but what the eating could teach me. I saw almost immediately that every time I lost weight, I flung myself at unavailable men and then got consumed by the drama of convincing someone who didn’t and would never want me to want me — which, being an impossible task, took up quite a lot of time.

I felt so unattractive at eighty pounds over my natural weight that flinging my body hither and thither was out of the question. And so I joined a writing class and started to write daily — something I’d longed to do since fifth grade — and quickly understood that if I got involved with yet another unavailable man, my creativity would focus on inventing interesting ways to capture he-who-had-no-interest-in-me. I decided to pour that creative energy into writing instead.

When I realized that I could do for myself what eating had been doing, I realized I’d been attempting to get through to myself with food, and vanilla fudge ice cream lost its allure. I suddenly understood that the power was mine to have, even if I gave it away to food — and I never went back to dieting or believing I was out of control again.

When we don’t either understand or believe that the weight has served a crucial purpose, we can feel as if having a thin body is like being shot into the open sky without a spacesuit. We are supposed to know how to breathe without a mask, move in a body that is no longer weighted down, relate to people without layers of padding. And we are supposed to feel thrilled about the whole process even when the pounds we shed served us in oh-so-many ways.

If you ask a group of people who want to lose weight whether they’d find being thinner and having more energy threatening, you would hear a unanimous “No.” But you would be asking adults, and that which wants to stay hidden is young. The proof is not in what people say they want, but in what they do. Not in their wishes, but in their actions, which consistently lead to the spectacularly dismal results of maintaining weight loss.

And while it is the adult who decides to limit her food or substitute good fats for trans fats, it is the ghost children — the ones that hid in the closet when our parents were fighting, or whose mother died when we were ten — who sabotage the results.

If even just a part of us is constellated around a painful story from the past, if we haven’t named or allowed the feelings that accompany that story their due, then losing weight is like telling a small child that everything on which her survival depends has been ripped away. Not exactly a recipe for success.

The heart of any addiction — drugs, alcohol, sex, money, food — is the avoidance of pain coupled with the unwillingness to acknowledge that both the behavior and its consequences serve us even as they destroy our lives. They keep us distracted from the original pain by creating another, possibly life-threatening situation. When we have to focus our attention on not driving while drunk, or having an operation to limit the food we eat so that we can walk, we have little time or interest in naming and meeting feelings we’ve been exiling for thirty or forty years.

Losing weight may indeed bring up fear of being overwhelmed by the very feelings you’ve used food to exile. But so what? Fear isn’t a monster; it’s a feeling. And like any feeling, it passes. Fear can be felt, held, dissolved by naming it, feeling its location in our bodies. Instead of avoiding fear we can do what is counterintuitive: welcome it and notice that the part that allows the fear is much bigger than the fear itself.

Maintaining weight loss isn’t only about what we eat. It comes back to what we want from our brief time here on earth. It’s about making a commitment to act in ways that match that desire, including our relationships to people, the work we do, the food we eat — and not giving ourselves the wiggle room of thinking we can go on a quick diet and then pay attention to what drives us to food. But how we get there is who we will be when we arrive there. If we deprive and shame ourselves with food (or any other area of our lives), we will be deprived, ashamed beings who might also be thin for five minutes.

“Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows,” David Foster Wallace wrote. “Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me… The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors.”

Choosing to keep struggling with food, whether it’s our way up or down the scale, is a choice to stay in the burning building of suffering while telling ourselves we can’t help it. The other choice is to jump from the burning building and discover, according to Chogyam Trungpa, that “you’re falling through the air, nothing to hang on to, no parachute. The good news is there’s no ground.”

Adapted from This Messy Magnificent Life, Scribner 2018