Taking on the USDA One Penny at a Time with Gunnar Lovelace – #323

What You Will Hear (note: timestamps represent audio, video may differ)

- 0:00 – Cool Fact of the Day

- 1:03 – FreshBooks

- 2:50 – Introducing Gunnar Lovelace

- 3:52 – Roots & starting Thrive

- 5:35 – What is a co-op?

- 8:12 – The right stuff vs. what is marketed as healthy

- 15:27 – Working with local farmers

- 23:59 – Vertical integration & mass farming

- 28:23 – The grocery supply chain

- 30:06 – Quality food vs. quantity

- 36:08 – Being a hypochondriac

- 42:00 – Voting’s importance in food

- 48:18 – Shooting on McDonald’s & fast food reform

- 51:00 – Disruptive technology

- 51:00 – Top 3 recommendations to kick more ass and be Bulletproof!

Featured

FreshBook.com/bulletproof How You Heard About Us – Bulletproof Radio

Resources

Bulletproof

Questions for the podcast?

Leave your questions and responses in the comments section below. If you want your question to be featured on the next Q&A episode, submit it using our Podcast Voicemail! You can also ask your questions and engage with other listeners through The Bulletproof Forum, Twitter, and Facebook!

Subscribe To The Human Upgrade

In this Episode of The Human Upgrade™...

BOOKS

4X NEW YORK TIMES

BEST-SELLING SCIENCE AUTHOR

AVAILABLE NOW

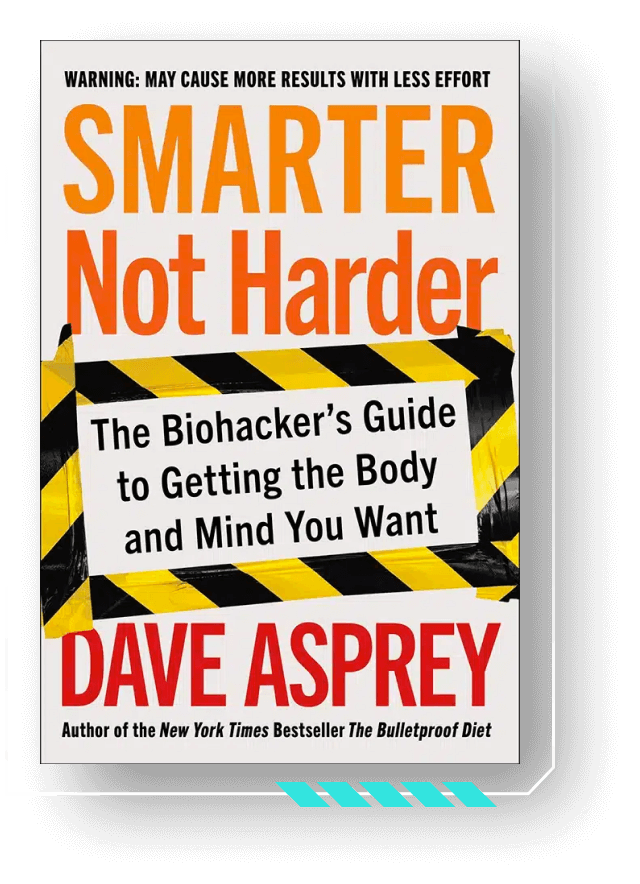

Smarter

Not Harder

Smarter Not Harder: The Biohacker’s Guide to Getting the Body and Mind You Want is about helping you to become the best version of yourself by embracing laziness while increasing your energy and optimizing your biology.

If you want to lose weight, increase your energy, or sharpen your mind, there are shelves of books offering myriad styles of advice. If you want to build up your strength and cardio fitness, there are plenty of gyms and trainers ready to offer you their guidance. What all of these resources have in common is they offer you a bad deal: a lot of effort for a little payoff. Dave Asprey has found a better way.