When it comes to nutrition and mainstream magazines with lots of ads from junk food companies, journalists sometimes seem to be oblivious to the research they write about.

Take Time Magazine in particular. In 1985 they tried to convince you cholesterol and saturated fat caused heart disease, now in the latest edition they’re trying to convince you that “It’s the calories, stupid.” (For the record, we only called them stupid in our headline since they called you stupid in theirs. 🙂 )

Most of the population doesn’t have time or interest to obsessively research the latest health information. They depend on the credibility (or lack thereof) of news organizations and mainstream health authorities. People who’ve done the research can usually find the truth, but it’s the people who are trying to be healthy without spending every waking moment on PubMed who suffer when the factory food industry backs articles like this one.

Most people know that a lot of what they see is inaccurate, but there are other stories that play on people’s minds and confuse them. Those misleading stories simply beg for a clear, science-based analysis.

On January 4th, Sora Song of Time Magazine published an article called, “It’s the Calories, Stupid: Weight Gain Depends on How Much — Not What — You Eat.” This is one of those articles.

The article focused on a recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association titled,

The goal was to find how over consuming protein or fat affected total weight gain and lean body mass. Basically, does eating more of protein or fat have a metabolic advantage over the other macronutrients?

Sora Song, an editor for Time Magazine, writes, “…it’s not what you eat but how much that matters when it comes to body weight.”

Like many people, she assumed that the only variable when it comes to food is the number of calories, which ignores the role of macronutrients like protein, starch, and fat, and ignored the outcome of the study. Coincidentally, if it was true that the only variable that mattered was how much you ate, you could eat a low carb diet of damaged seed oils, fructose, soy protein, and whole grains and it would have the same effect as a high carb diet of sweet potatoes, seafood, and coconut (like the Kitavans). As research on the Kitavans shows, the difference between these two diets is obvious.

That difference illustrates a key point – that’s in not all about the calories. While a high carb diet is not necessarily bulletproof, it’s a lot better than a high toxin diet -regardless of the macronutrient composition.

This is easy to test for yourself – simply try a diet with optimal macronutrients and low toxins at the same time. Wait 2-3 weeks, then look in the mirror. Nature doesn’t lie.

The Study

Three high calorie diets were tested in a group of people between the ages of 18-35. They had a BMI of 19-30, with some people being normal weight, and others being overweight. The participants were placed on three high calorie diets with varying amounts of protein and fat.

Group 1: “Low Protein”

- 6% of calories from protein.

- 42% of calories from carbs.

- 52% of calories from fat.

Group 2: “Normal Protein”

- 15% of calories from protein.

- 41% carbs.

- 44% fat.

Group 3: “High Protein”

- 26% of calories from protein.

- 41% of calories from carbs.

- 33% of calories from fat.

Carbohydrates were kept the same for each group, with the difference in energy intake being accounted for by fat. There was no low-carb group. Each group was fed 884-1022 excess calories per day, or 40% over their “maintenance” requirements. (Ignoring the fact that maintenance requirements are a myth, as I wrote in this response to a NY Times piece which said the opposite of today’s Time Magazine piece.)

The subject’s body compositions were measured with DEXA scans twice a week. DEXA scans are the most accurate method to date for determining body composition (hats off to the researchers for doing it right). Resting energy expenditure and total energy expenditure were measured throughout the study, but not in a calorimetry lab.

Results

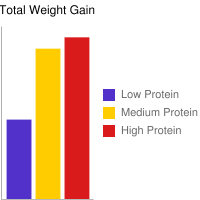

“Overeating produced significantly less weight gain in the low protein diet group compared with the normal protein diet group or the high protein diet group.”

The low protein group gained almost half the weight of the other groups.

Total Weight Gain

Low Protein (5%): 3.16 kilograms.

Medium Protein (15%): 6.05 kilograms.

High Protein (25%): 6.51 kilograms.

Good golly. The headline says that the only thing that matters is how much you eat, but the research says the opposite. Good thing there’s probably an ad for Pop-Tarts or Kellogg’s Kashi to distract me.

According to the headline, if the subjects are eating the same amount of excess calories, they should gain weight proportionally. They didn’t. This directly refutes the premise that “it’s all about the calories.” If changing the macronutrient composition of the diet alters weight gain, then saying “…it’s about the calories, stupid” is a blatant misinterpretation (not to mention, a little insulting). It’s obviously not all about the calories if one group gained less than the other two. I’m not advocating a low protein diet, but this does refute the headline!

Body Fat vs. Lean Muscle: High Protein Wins

If a calorie is a calorie, then all three groups should have gained the same amount of weight. They also should have experienced the same changes in body composition. They didn’t.

All three groups gained the same amount of body fat, which was about 50-90% of the excess weight. The low protein group gained almost all fat (90% of excess calories) while the other two groups gained about 50% fat and 50% muscle. The low protein group also lost about 750 grams of lean body mass. To put things another way, overfeeding on a moderate to high protein intake builds muscle and fat, while overfeeding on a low protein diet builds mostly fat. The low protein group gained less total weight, but what they gained was almost exclusively fat.

In the face of protein restriction, the subjects’ bodies were scavenging proteins for organ function and repair. Despite no exercise during the study, higher protein intakes are generally beneficial for supporting tissue regeneration in any form. By limiting protein intake to an absurd degree (6% of total calories), it became hard to support muscle growth and organ size. As a result, the medium and high protein groups gained more lean mass. Since muscle weighs more than fat, this could explain the difference in total weight gain.

The high protein group also had a higher resting energy expenditure. This isn’t surprising given the high thermic effect of protein over carbs and fat. Muscle tissue it also more metabolically active, which would use more energy and increase caloric expenditure even further.

The extremely low levels of protein were not enough to maintain lean muscle mass. A protein intake of 6% of total calories is lower than anything recommended on the Bulletproof Diet, or any diet designed to optimize health.

Diet Quality Matters, or Why Butter & Trans-Fats Aren’t The Same Thing

“The eating plans… included food you’d find in the typical American diet: eggs, bacon, biscuits or cereal for breakfast, for instance; tuna salad, turkey sandwiches and chips for lunch; pasta, rice, pork chops or casserole for dinner, accompanied by salads and fruit; and plenty of baked goods, candy and other processed sweets for snacks and dessert.”

As usual, no attention was given to the quality of the diet. Biscuits, cereal, bread, chips, rice, casserole and “…plenty of baked goods, candy and other processed sweets for snacks and dessert” could easily have contributed to fat gain. All of these foods are extremely inflammatory, and inflammation shows up as weight gain on the scale far more quickly than fat does.

Inflammation affects weight gain and body composition directly and indirectly, as does malnutrition. It’s possible the subjects became slightly malnourished in vitamin D, magnesium, and other trace nutrients. It’s almost guaranteed they were deficient in vitamin D, as all the participants were locked in a metabolic ward for 12 weeks with little exposure to sunlight.

As an example of how micronutrition effects body composition, magnesium deficiency can exacerbate insulin resistance. Without enough magnesium you can get fatter during overfeeding while eating the same amount of calories. This study was designed to reflect the average American diet. As such, it’s safe to say the subjects were magnesium deficient, since 80% of the U.S. population is deficient in magnesium.

Magnesium is also an important cofactor for vitamin D, which is why people can develop rickets with replete vitamin D levels. Vitamin D affects over 1000 different genes in the body, so it’s obvious how important proper nutrition really is. Again, a calorie is not a calorie, stupid. (and please accept my apology in advance. I’ve learned that it’s poor form to insult one’s valued readers.)

What does this study prove?

Since carbs were kept the same for all three groups, it’s impossible to say whether or not altering carb intake changes body composition or weight gain (based on this study). It would be nice to see the researchers look at how different amounts of carbohydrate intake altered body composition and total weight gain.

It’s true that varying protein and fat intake does not produce vast changes in body mass (3 pounds over 12 weeks isn’t much), but it does have an effect on the kind of tissue gained (muscle vs. fat).

Despite lack of control over food quality, this study was pretty sound. It supported the idea that a higher protein intake leads to better retention of muscle tissue during overfeeding. In other words, inadequate protein leads to muscle loss during overfeeding. The problem is the way this study was reported. Instead of saying, “Macronutrients Matter: Or Why A Calorie Is Not A Calorie”, Ms. Song tried to use this study to prove the opposite point. Instead of using a good study to support the truth, the author tried to use it as proof of the standard dogma in regards to weight gain – that it’s all about calories.

Dr. George Bray, the author of the study, also disagreed with Ms. Song,

“Among persons living in a controlled setting, calories alone account for the increase in fat; protein affected energy expenditure and storage of lean body mass, but not body fat storage.”

In simpler terms, protein intake changed how nutrients were partitioned in the body. Eating more or less protein directly changed the way nutrients were stored, supporting the notion that it is not all about calories.

An even better conclusion would have been,

“A high protein intake is superior to a low protein intake for preserving and increasing lean body mass during overfeeding. Changing macronutrients has very different effects on body composition and total weight gain, despite an isocaloric, clinically controlled setting.”

It would be nice to see a study change the carbohydrate content of the diet instead of just protein and fat. Since carbohydrates were the same for each group, and each group gained the same amount of fat, you could even say fat gain is proportional to carbohydrate intake during overfeeding. Oops.

When carbs are limited to around 100-120 grams a day (or less if you’re trying to lose weight) on something like the Bulletproof Diet, you may see a gain of almost pure muscle (which is exactly what I’ve found through personal testing).

When you add the variable of food quality, things become even more complex. While it’s unlikely a clinical trial will ever be run on Bulletproof Diet, I think the results would be profound. The Bulletproof Diet has an optimal macronutrient composition, as well as the added benefit of as few toxins as possible. In most studies, no attention is given to the quality of food being consumed, only the quantity. Macronutrients and food quality matter – it’s not all about calories.

This study showed that changing macronutrients does affect weight gain and fat loss even in the presence of poor food quality. If more attention had been paid to where the calories came from (qualitatively), it’s likely the results would have been even different.

Until major media outlets report studies in a fair and unbiased manner, people will remain confused – and fat.

Some background research for this post may have been conducted by Bulletproof staff researchers.