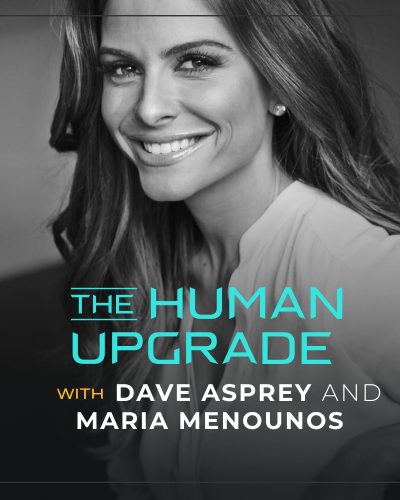

EPISODE #1091

Hacking Happiness: How to Leverage Evolutionary Biology to Live the Good Life

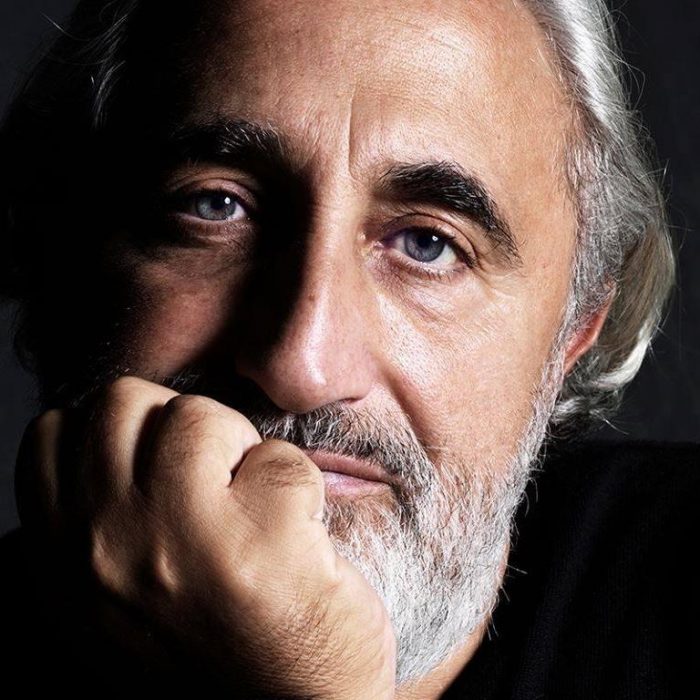

Dr. Gad Saad

In this conversation with the esteemed Dr. Gad Saad, a professor of marketing at Concordia University and author of The Saad Truth About Happiness, we explore living the life you truly desire, the role of anti-fragility in happiness, and the biological differences in male and female behaviors.

In this Episode of The Human Upgrade™...

In today’s episode, we’re joined by Dr. Gad Saad, a professor of marketing at Concordia University’s John Molson School of Business. More significantly, Dr. Saad has spent a decade as the research chair in evolutionary behavioral sciences and Darwinian consumption. He’s a prominent voice challenging political correctness and its associated oppressions.

Beyond his extensive research and academic accolades, Dr. Saad reaches out to a broader audience, sharing his insights through his popular blog, YouTube channel, and podcast. As someone deeply interested in challenging harmful ideologies, I’ve taken note of his impactful book, The Parasitic Mind. Today, I’m particularly eager to delve into the findings of his latest release, The Saad Truth About Happiness.

In our discussion centered around his newest book, we delve into the evolutionary aspects of happiness. As someone who’s written extensively on longevity and aims to live to at least 180, I believe in the importance of happiness as a skill. With Dr. Saad, we explore living the life you truly desire, the role of anti-fragility in happiness, and the inherent biological differences in male and female behaviors.

It’s crucial, especially in today’s climate, to understand the triggers that may be rooted in our biology or false belief systems. Drawing from personal experiences, I can vouch for the invaluable insights in Dr. Saad’s book. Listeners, it’s a must-read for those keen on understanding and cultivating happiness.

“Science, if practiced properly, is nothing but play.”

DR. GAD SAAD

(03:50) Decision-Making in Relationships & Academia

- Must-have ingredients for happiness

- The impact of your relationship on happiness

- When do you make the decision to decouple from a relationship?

- How statistical decision theory applies to academia

- Read: The Parasitic Mind by Dr. Gad Saad

- The garage band effect that occurs in academia that prevents action-taking

- Why academics who go on the Joe Rogan Experience are ridiculed by peers

- Read: The Laws of Human Nature by Robert Greene

- Behind the scenes of our interviews on Joe Rogan’s podcast

- Joe Rogan Experience #275 – Dave Asprey

- Joe Rogan Experience # 2012 – Dr. Gad Saad

- Happiness in moderation vs. living high on life

(19:40) Perfectionism, Criticism & The Genetics of Happiness

- Navigating the inverted U curve for perfectionism

- Handling the two groups of critics

- The Science Behind Just One Mold Toxin in your Coffee by Dave Asprey

- The genetics of happiness

- Applying the psychometric scale of internal vs. external locus of control to happiness

- How our evolutionary behaviors can become maladaptive in modern society

- Exploring how having children impacts happiness

- What the research shows about how to choose a long term partner

(47:10) Evolutionary Insights on Mating, Cheating & Play

- The evolutionary roots of sexual variety seeking

- Why certain cultures tolerate women on the side more than other cultures

- The impact of birth control and hormonal changes on fertility and attraction

- Read: The Mating Mind by Geoffrey Miller

- The link between the ovulatory cycle and women’s beautification

- What increases men’s testosterone: a study providing context for the mid-life crisis

- Why play is essential for happiness

- The re-education of Jordan Peterson

- Read: The Saad Truth About Happiness by Dr. Gad Saad

Enjoy the show!

LISTEN: “Follow” or “subscribe” to The Human Upgrade™ with Dave Asprey on your favorite podcast platform.

REVIEW: Go to Apple Podcasts at daveasprey.com/apple and leave a (hopefully) 5-star rating and a creative review.

FEEDBACK: Got a comment, idea or question for the podcast? Submit via this form!

SOCIAL: Follow @thehumanupgradepodcast on Instagram and Facebook.

JOIN: Learn directly from Dave Asprey alongside others in a membership group: ourupgradecollective.com.

Websites: danielamenmd.com and www.amenclinics.com

Discover Your Brain Type: www.brainhealthassessment.com

Instagram: www.instagram.com/doc_amen/

Twitter: www.twitter.com/DocAmen

Facebook: www.facebook.com/drdanielamen/

YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/AmenClinic

Previously on this podcast:

[00:00:00] Dave: You’re listening to The Human Upgrade with Dave Asprey. Today, our guest is Dr. Gad Saad, who’s a professor of marketing at Concordia University’s John Molson School of Business. But the reason I want to talk to him is that for a decade, he has held the research chair in evolutionary behavioral sciences and Darwinian consumption.

[00:00:25] And this is what makes me happy. He’s one of the best-known public intellectuals fighting political correctness and the tyranny that comes with it. If you’ve been listening to the show for any of the last 1,000 episodes or following me on social, you might have noticed that political correctness isn’t my favorite thing.

[00:00:46] And for the record, I do not vote for any party. I don’t even believe in parties in general. I think they’re a way of removing choice and giving you the illusion of control. So yes, I will just say it. If voting changed anything, they would have made it illegal a long time ago, but it sure does feel good.

[00:01:02] There. Now, many people are offended, which is the whole point of political correctness. It’s okay to disagree with me and still listen to what I have to say. And if you hate me because of anything I say, you should tell all of your friends and stop listening right now. I got that out of the way.

[00:01:18] You have a new book, though, that isn’t about political correctness, and that’s what I wanted to really talk with you about. I know we’re going to make some jokes that are inappropriate or something, but The Saad Truth About Happiness: 8 Secrets for Leading the Good Life. And this is because you’re an evolutionary behaviorist. The reason this is fascinating to me is that I believe we have an operating system in our meat. I call it the meat operating system in my most recent book.

[00:01:43] Dave: What that means is that you’re going to learn about things like why happiness makes you live longer. And if you’re a longtime listener, you know I’ve written one of the major books on longevity. I’m planning to be a guy who lives to 180 at least. Yes, I may be aggressive on that, but I’m okay to be aggressive.

[00:02:00] I’m also okay to have the world’s most expensive pee from the 150 supplements I take per day. That’s all good. But who cares if you’re not happy? Because happiness is a skill. We know some of the ingredients of happiness, but I don’t think you’re going to find any expert on earth who understands happiness from an evolutionary perspective like Gad does.

[00:02:24] We’re going to talk about how to live the life you want, not the life that you were programmed to expect. And we’ll talk about how anti-fragility makes you happy, because it’s topical. Actually, two nights ago, I think it is now, I decided at 9:30 at night that I didn’t want to be locked in the gates of Burning Man in the middle of the worst mud storm I’ve ever seen.

[00:02:49] So I decided to throw on a backpack and slog six miles in the middle of the night, including crossing two almost rivers, and walk out of Burning Man so that I could do this interview, which I did. And I don’t regret it one bit, but the fact that I could throw on a backpack and walk until 12:30 at night on a moment’s notice is part of the physical side of anti-fragility, but there’s also the my-feelings-were-hurt-and-I-can’t-function side of anti-fragility, and I’m going to go deep on that in this interview. That said, it is an honor to have you on the show, Gad.

[00:03:26] Gad: Oh, it’s a pleasure to be with you, Dave. Thank you for rushing back from Burning Man to be with me.

[00:03:31] Dave: You are most welcome, and I’m going to do my best to say your name, which is between God and Gad, and right in the middle. So if I call you God, it’s entirely accidental, and if I call you Gad, I apologize in advance.

[00:03:44] Gad: No worries.

[00:03:45] Dave: You mention in your book that there’s no magical formula for happiness, but that there are ingredients that are necessary. What are the ingredients for happiness that you must have?

[00:03:56] Gad: I think that when you wake up in the morning next to someone, if that person that’s next to you is someone who you feel comfortable with, whom you trust, whom you love, you’re climbing Mount Happiness nicely. Then if you go off to work and pursue a job that gives you purpose and meaning– I wake up every day and rub my hands in anticipation with a gleeful, desire to pursue the days. Today I’m speaking with Dave Asprey. Did I pronounce that right by the way? Asprey?

[00:04:30] Dave: Yeah.

[00:04:31] Gad: Asprey, okay. Uh, I might be talking to some graduate students. I might be working on the idea for my next book. There are all sorts of immersive things that I face on any given day. Once I finish my work, if I return to that bed, next to that person that I love, then boy, I’ve pretty much seemed to have cracked much of the code of happiness.

[00:04:52] And so that’s why very early in the book, I have a section, I guess we’ll get through many of the other recipes, but I have a whole chapter on choosing the right spouse and the right profession as two of the most fundamentally important decisions that you’ll make that either will impart great happiness or great misery upon you. And we can drill down each of those if you’d like.

[00:05:14] Dave: Are you an advocate of people ending their marriages if it’s not working so they can be happy?

[00:05:20] Gad: By the way, I don’t think I’ve discussed this publicly, but just your question necessitates that I share this. My parents probably hold the all-time world record for separating after the longest marriage. I’m almost certain they probably hold the world record. They were married in 1950 when they were both very, very young. My father was about 20. My mother was 16. This is old-school Middle East. My mother had three kids by the time she was 19, and then she had me 10 years later. I’m the youngest of the family.

[00:05:55] Dave: My daughter is 16. I can’t even imagine.

[00:05:58] Gad: Exactly. They separated after 60 plus years of marriage. So to answer your question, I think that, yes, you can extricate yourself from an unhappy situation at any point. Life is too short to stay in a happyless marriage, but hopefully there are ways that we can ride out some of the difficulties that most marriages might face.

[00:06:23] Dave: Very well put. I was married for 17 years, and my former wife and I consciously uncoupled, where we’re still friends, we’re co-parenting, the kids are happy, and we care for each other, but just decided that we weren’t the right person for the other person’s happiness, uh, without any blame, a nasty divorce, and all of that because happiness is important.

[00:06:46] And if you’ve done all the work and what’s left is just incompatibility, that’s okay. And moving on, I think, is a mature but very difficult thing to do. And some people get very offended at that because they feel like, well, maybe that could happen to me. Let’s be politically incorrect. It could happen to you. So maybe you should work on your marriage and work out to the point that if it does happen to you, that you’re glad it happened to you.

[00:07:10] Gad: I can actually link our current conversation to 30 years ago when I defended my doctoral dissertation. My PhD dissertation was on something called stopping rules, which is the idea that, when is it that you’ve collected enough information to stop acquiring additional information and commit to a choice?

[00:07:31] So let’s suppose I’m choosing between two political candidates, or two cars, or two mates that I might marry. I don’t look at all of the available information. I look at some subset, and at one point, I say, I’ve acquired enough to choose Mazda, to vote for Hillary Clinton, to marry this person. Well, we can apply that exact framework to the question that we’re addressing right now, which is, when is it that you have acquired enough information to stop and, as you put it, decouple from the relationship?

[00:08:05] And so, in a sense, if I took my own dissertation, I think that’s why my dissertation work was quite important, because this idea of when do you stop acquiring information and commit to a choice, whether it be choosing something or, in this case, rejecting something, getting out of a marriage, is a fundamentally important decision when you’re making choices.

[00:08:28] Dave: There’s some really toxic words that are at the end of almost every article on PubMed, which is the place you go to read all the scientific papers. And it’s, before you do anything, more research is needed. And the reason I think I’m going to live to 180 is that I’m the guy who reads the paper and takes action, versus the guy who says, well, until I have more information. Why do you think academics are afraid to do anything until they have more research? It seems like they haven’t read your paper.

[00:08:55] Gad: Yeah, that’s a very good way of analogizing it because the original work on which my dissertation was based comes from statistical decision theory, a gentleman by the name of Abraham Wald, where he actually applied it very much in the context of what you’re talking about PubMed.

[00:09:12] So when is it that I have collected enough of a sample size to be able to unequivocally state that there is now enough evidence in support or in refutation of my hypothesis? Or think about it in the context of a manufacturing system. How many products must I sample before I can say that the manufacturing process is quality controlled or yields too many defective products?

[00:09:40] So this idea of, you don’t need to acquire ad infinitum information before you make– and as a matter of fact, we don’t do that. Because if we did that, we would be stuck in choice paralysis forever making only one decision. Rather, we only look at some subset, but that subset must get us over the threshold so that I feel sufficiently confident to marry this woman, buy this Mazda, get rid of this employee, and so on.

[00:10:09] But to your question about scientists, I think scientists are very, very risk averse in the pronouncements that they make, which by the way, is one of the reasons why they’re usually not very good public speakers, because they have to put 73 qualifiers before every sentence. It may be, it’s almost, we believe that, it could be, the evidence suggests. And once you put so much equivocation, then most statements have no longer any actionable meaning.

[00:10:39] Dave: It’s also funny that many academics who join the world of educating the public, they get looked down on by other academics. You didn’t put enough qualifiers in there. And besides, you just sold a million books and helped a million people. You get this, you’re not a real academic. Do you ever face that?

[00:11:00] Gad: Oh yes. Yes. That’s a great question. So in the first chapter of my previous book, this guy right here I’m pointing to, The Parasitic Mind, I call what you just described, the garage band effect. So if I am a starving artist, musician, playing in my garage in front of my girlfriend and my mom, then I’m a struggling artist who loves– I’m passionate about my art.

[00:11:26] If I then have a breakout hit on the billboards, and now I play at Wembley stadium in front of a 1,000 people, I’m a sellout. And so academics are exactly those who succumb to the garage band effect. And I’ll give you a specific story. In 2017, I had been invited to speak at, uh, Stanford University’s business school, certainly one of the meccas of academia, to talk about some of my evolutionary psychology work as applied to consumer behavior and so on.

[00:11:57] The night before my talk, the host who was hosting me that evening, we went out to dinner. He’s a fellow professor who then became an editor of a major journal in my field. He said to me, uh, oh, I was doing some searches to get a sense of your background, your profile, and I didn’t know you were friends with Joe Rogan, and you go on his show, and so on. I said, yeah. He goes, yeah, we don’t condone that at Stanford. I said, you don’t condone what at Stanford?

[00:12:27] Dave: Don’t tell Andrew Huberman. By the way, he was guest number 400 on this show before he had a show, right?

[00:12:33] Gad: Exactly. And so he said, we don’t do research so that it can be sexy, so that we can appear on Joe Rogan. I said, well, I don’t do that research either, but surely it is better to be able to both do great research that is peer-reviewed, and then take that show on Joe Rogan so you can popularize it to 20 million people. I can do both of these. But in his mindset, he was looking down at me because I was a sellout. I was a Joe Rogan friend.

[00:13:01] Dave: Yeah, if they want to say you’re a sellout because you took the university’s research and made it popular, it begs the question, what is the purpose of the university’s research? As a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, I got really frustrated. I realized the best technology never wins because it’s easy to invent things. It’s very hard to get people to use them.

[00:13:21] And if you invent it and no one knows because it’s kept in your garage and kept it a secret because you suck at marketing, you’re also a bad inventor. So to any academic listening, by the way, shame on you for listening to a podcast. This is not a journal. And number two, you got to do the hard and ugly work. I love writing my books compared to publicizing my books. I’ve been on hundreds of podcasts to say the same exact thing because that’s our job, if our thoughts are worthy, to get them out there. And if they’re not worthy, then don’t write them down.

[00:13:51] Gad: But to our point, if I can, I think the reason why they have that pension to denigrate, it’s the classic ego defensive strategy. Because the typical academic has mastered the publishing game in peer-review journals. And I’m not denigrating that. As a professor, I am tasked to create new knowledge and publish it in top journals.

[00:14:11] That’s great. I still love it. I love to do that. But that person has mastered that particular medium, but it takes a completely different set of social skills to be able to go on Joe Rogan and roll with those punches. Now, if I am this weasley, shy academic, I’m not going to be able to go on Joe Rogan. So I could do one of two things. I could either recognize that I don’t have that skill set, or I could, with complete professional envy, look at the one who can do it, and say, you suck. You’re not a real academic because you’re friends with Joe Rogan. So it’s classic ego defensive stuff.

[00:14:51] Dave: Ooh, I love how you call it out. Probably the best non-academic academic who writes about envy and jealousy is Robert Greene, the guy who wrote 48 Laws of Power, is a friend who’s been on the show a couple of times. He has a chapter in the Laws of Human Consciousness that says, when someone is feeling envy or jealousy, when you tell them good news, they’ll briefly scowl, and then they smile and say, good work. So you can spot the people like that. And those are the academics who scowl when they hear you’ve been on Joe Rogan and say, we looked down on that, but the real reason is they didn’t get to go.

[00:15:26] Gad: As the saying goes, I hope I don’t butcher it, whenever my friend succeeds, something in me dies. That’s envy.

[00:15:34] Dave: Ooh, that’s a great quote. Now I got to ask you this. So every time I went on the Joe Rogan show, he was inhaling right before the show started and trying to hand me the joint, and I’m like, I can’t hit that or I’m going to be stupid on the interview. So did you smoke before the camera rolled?

[00:15:51] Gad: Uh, it’s funny. I’ve never ingested, consumed a single drug in my life. I’ve never even taken a single puff of a cigarette. And I actually mentioned this once on Joe’s show, and he was surprised. And I can’t remember if I had stated this, and if I haven’t, let me state it here. I don’t need drugs. I’m high on life. Life is my drug. Hence, that’s precisely why I wrote that book, because the majesty of life is a– I’ve never taken crystal meth or heroin, but I’m on a perpetual heroin high that’s called life.

[00:16:26] Dave: It’s true that life makes opiates, and that’s what you’re getting from heroin, so when you’re doing it right, you can turn that on, but it probably isn’t on– in fact, research shows it’s not on all the time. You cycle up and down. And maybe that’s tied into this idea I don’t really like, but it’s part of the beginning of your book about moderation and something called an inverted U curve. So talk to me about moderation versus living high on life, which doesn’t sound very moderate.

[00:16:54] Gad: Right. Thank you for that question. So the idea of everything in moderation is, of course, one that the ancient Greeks were very adept at reminding us, but they certainly were not the only ones. Buddhism has middle way, which is exactly the same idea. Maimonides, the Jewish philosopher and physician to the Sultan almost a 1,000 years ago, said the same thing.

[00:17:16] So what I did in that chapter, Dave, is I demonstrated that most phenomena that you could think of, whether they are at the neuronal level, at the individual level, at the economic or social level, follow this inverted U. Inverted U simply means that for whatever phenomenon you’re looking at, too little of that is not good. Too much of that is not good. And then life becomes the pursuit of that middle way, that sweet spot.

[00:17:43] So let me give you an example of such a phenomenon where I happened to be on the wrong side of the curve. So even for the guy who wrote the book on happiness and the chapter on moderation, that doesn’t mean that I have cracked it for all of the phenomena and issues that I face.

[00:17:59] So perfectionism, the trait of perfectionism follows an inverted U shape. If you’re not, in the least bit, a perfectionist, let’s say as an author, then you won’t be attentive to details. You’ll have tons of errors, your references will be wrong. As an author, you have to be attentive to details.

[00:18:17] On the other hand, if you are where I am on the curve, on the too perfectionist end, then you end up spending two weeks going over the galley proofs. For those of you who don’t know, the galley proofs is the final version that you receive. This is your last chance to find any errors. After that, it’s going to press, and your error will be immortalized. And that makes me incredibly anxious.

[00:18:40] And so I spend way too much time reading every single strike of the keyboard, poetically stated, because I am so fearful that there might be a comma out of place, or a typo wrong, or a reference had the wrong issue journal, whatever. And so had I been able to better temper myself on perfectionism so I come to the sweet spot, then I might have gained that one extra week where I only found two typos. Those two typos were not worth my extra week of doing this. And so even the one who recognizes that life is about finding the sweet spot, that doesn’t mean that we can extricate ourselves from that trap.

[00:19:22] Dave: Okay, I got to ask a really big question now. So I’m the kind of guy who will say, okay, I’m going to outsource perfectionism. I’m going to hire perfectionists to review my book. And in order for me to do that, it requires trust. And these are evolutionary things. These are all feelings that are in our biology, not necessarily in our conscious mind.

[00:19:44] But the more trusting you are, uh, the more likely you are to attract a narcissist or a sociopath into your organization who will take advantage of your trust. But if you’re untrusting, what’s that going to do to your happiness, right? You’re not going to be very happy if you don’t trust anyone. So how do you navigate that inverted U curve to trust only some of the time and still be happy?

[00:20:04] Gad: I can, again, apply what you just asked to my own academic career. And I mentioned it briefly at one point in the current book, in the happiness book. So part of being a productive academic is to set up networks of collaborations. In this case, you’re not subcontracting your work to another. You’re an equal collaborator.

[00:20:25] But given the exacting code of perfectionism and ethics that I have, I’ve ended up walking away with many opportunities for collaborations because I wasn’t sure, to your point– you use the word trust– that I could trust that person or that lab enough to meet my standards of perfectionism. And in doing so, I lost the opportunity to publish 20, 30, 40 additional papers, which otherwise I would have.

[00:20:57] Now, let’s put it in the context of the inverted U. If you’re someone who never wishes to collaborate, that’s certainly going to affect your productivity, and so maybe that’s bad. If every single paper you ever publish is a sole-authored paper, boy, you’re losing an opportunity to create interdisciplinary teams and so on that might help you crack a problem that otherwise you wouldn’t have been able to crack if you were working alone.

[00:21:21] If you are too much of a collaborator whereby there is no mechanism of vetting people, then you end up, for example, let’s take an extreme case, where you are on a paper with some people who ended up being so unethical that they doctored their data. That’s one of the things that scares me so much.

[00:21:39] How do I know, when I’m working with someone, that they’re not scammers? Now, my name is going to go on that paper. So there is, again, a sweet spot. In my case, I’ve always been on the wrong side, in that I’d rather be able to sleep well at night knowing that any paper that I’ve produced passes– I tell my students that it passed the Gad kosher test. Only then do we send the paper. And so they’ll write back to me, yes, Professor, it passed the Gad kosher test. So it’s a lifelong struggle to constantly know whether you’re on the wrong side of those curves or whether you’ve hit the sweet spot, and I struggle with it just like anybody else.

[00:22:19] Dave: I’m happy you talk about that. I do too. I care so much about the books that I write and about truthfulness and just saying, well, here’s how I’ve noticed it works, but I don’t have a paper for it. The paper might come out five years after the book is written, and that has happened, but you can say, try it, and see if it works, versus, we know this to be true because of these facts.

[00:22:41] How do you handle critics? When people come out and say, your paper was wrong, and you’re a bad person, and all the things that critics say, what’s your process for that and staying happy?

[00:22:49] Gad: So that’s a great question. It depends. There are two types of critics, one of whom don’t trigger me at all, and I’ll answer how I handle them, and another group that do anger me. So let me answer those first. The ones that upset me are the ones who are walking Dunning-Kruger effects. What does that mean?

[00:23:11] Dunning-Kruger, if you may know, is someone who is blissfully arrogant in their supreme ignorance. So it’s the perfect combination of, they’re completely imbecilic, and yet they’re really arrogant about being imbecilic. And of course, social media is populated with nothing but such types.

[00:23:31] So when someone writes to me and says, what is it that you study in evolutionary psychology? That’s just a bunch of quack science. That upsets me because that moron, from the safety of his basement, is engaging in a fundamental attack on decency because they have such hubris, they think they know so much. They know nothing.

[00:23:54] They’re taking someone who spent 30 years of their life studying this stuff, and they’re saying, no, no, you’re full of– so those guys usually upset me because they’re violating, in my view, codes of human decency of how to behave properly, how to engage in a proper debate. The other folks who genuinely criticize me, let’s say in the pursuit of– fellow academics, or social critics–

[00:24:20] So let’s suppose I’m trying to demonstrate to you that toy preferences are not socially constructed, meaning that little boys prefer certain toys and little girls prefer certain toys, and that’s not because of social construction. There are some evolutionarily relevant biological mechanisms that explain these universal sex specific toy preferences.

[00:24:44] Now, why am I using this in the response to your question? Because I will get an academia, many critics of mine, of my evolution psychology work, who are social constructivist. In other words, they argue that biology matters for the mosquito, the zebra, and the dog, but surely, biology doesn’t matter for consumers, Professor.

[00:25:03] Surely, it doesn’t apply for– but we transcend our biology. We are cultural animals. And so the way I’m going to now address those detractors is what’s in Chapter 7 of The Parasitic Mind. So there, what I do, Dave, is build what are called nomological networks of cumulative evidence.

[00:25:24] What’s a nomological network of cumulative evidence? It’s me trying to say, let me think about my critics to your question, my most vociferous dogmatic critics, what would be the evidence that I would need to amass for them to then concede the argument. And so what do I do? Let’s do it for toy preferences.

[00:25:49] I can get you data, Dave, from developmental psychology, that shows that children who are too young to have been socialized yet, in other words, they haven’t yet reached that cognitive developmental stage by definition, already exhibit those sex-specific toy preferences. So already that one line of evidence is very powerful.

[00:26:09] Oh, wait, wait, your mind is going to be a lot more blown than that. Hang in there. Fasten your seatbelt. So imagine in the middle of the network is the phenomenon that I’m trying to prove to you. You’re my detractor. You’re my critic. Okay, so now there’s one box from developmental psychology that’s quite convincing. Even if I stopped right there, I’ve done my job, but I’m not going to stop there because I’m going to put an epistemological noose around your neck by bringing in so many lines of distinct evidence that you’re going to drown in evidence.

[00:26:43] Okay. Number two, I can get you data from other species, from vervet monkeys, from rhesus monkeys, from chimpanzees, showing you that their infants exhibit the same sex-specific toy preferences as human infants. Now, you certainly can’t argue that mama and papa vervet monkeys are doing this because they’re part of the sexist patriarchy.

[00:27:09] So now I’ve got the new data from developmental psychology. I’ve got the new data from comparative psychology. Comparative means across species. But I’m going to go on. I won’t do the whole network, but I’ll do two or three more examples. Now, you might say, but wait a minute, though. You don’t have data from across cultures. Maybe there’s something unique about Western culture that makes boys prefer trucks and girls prefer dolls.

[00:27:32] All right, here I come with data from nomadic sub-Saharan cultures that are completely detached from Western society, and I can show you the research that shows that they exhibit the same sex-specific toy preferences. Then you, as my critic, comes, okay, well, that’s great. You’re starting to convince me, but you don’t have data from across millennia, Professor.

[00:27:55] Oh no, wait a second. I’ve got data from ancient Greece and ancient Rome, on funerary monuments, where on mausoleums, they have depictions of little girls and little boys playing with the exact same toys as we have today. So what am I doing in building this network? I’m showing you that across species, across disciplines, across methodologies, across cultures, across time periods, there is a triangulation converging to my position being the vertical one.

[00:28:26] So all this long-winded way to answer your question, how do I handle my critics, I build the normological network that squashes you into oblivion. So this is why whenever I debate someone, I have what’s called epistemic humility. When I know, I know. Good luck to you if you want to debate me. But you could ask me a million questions, Dave, where because I’m epistemologically humble, I’ll say, that’s a great question, Dave. That’s above my pay grade. I don’t know the answer to that. I haven’t built the normological network.

[00:28:58] Dave: Yeah, not knowing and knowing that you don’t know is a sign of having an ego under control. It’s interesting, um, there was a time a while ago, after I was on Joe Rogan, uh, a few times, where he had an investment in a company that was competing with mine. So there might’ve been some untruthful things about me said in order to, uh, harm my business interests.

[00:29:20] And my only response to them was just the same blog post. You can still find it. It’s called One Ugly Mug. Here’s 34 studies, that I didn’t pay for, validating that there is toxic mold in coffee, and it survives the brewing process, and it’s not good for you. So you can say I’m full of crap, that there isn’t mold in coffee or whatever, but that was my only response ever.

[00:29:43] It was just a link to the post and nothing else. Yeah, I had to do some therapy on the back end so I wasn’t pissed off all the time at unwarranted attacks, but sticking to the science and just being right is a really good thing. I got to ask you this too. Evolutionary, from what I can see in my neuroscience company, which is called 40 Years of Zen, and we’ve done 1,500 high-performance people’s brain waves and how to control them– so I’m really into this stuff.

[00:30:10] It’s abundantly apparent that when you see a five-year-old, again, this is evolutionary stuff. Five-year-olds don’t have that much stuff going on. Most parents have seen what I’ve seen, where– a famous family story– there’s a kid across a lake, casts and falls into the water, and then splutters, comes out, and says, you pushed me in.

[00:30:30] And you’re like, I was across the lake. You just seek to blame another. So our ability to see reality is highly influenced by our biology. So how do you know in these situations when you think you know that you actually know? Do you have some structured process for this, versus this is all your ego telling you you know because being wrong would be bad?

[00:30:51] Gad: Let me link your question to the genes or the genetics of happiness. So very early in the book, I make it clear that about 50% of individual differences in happiness scores stem from our genes, meaning that some of us are born with a sunny disposition. Some of us are born with a less sunny disposition.

[00:31:11] But that statement is actually one to celebrate because if 50% of our happiness stem from our genes, that means the other 50% stems from things that we can do to alter our pathway toward Mount Happiness. So I may start with a better sunny disposition point than you do, Dave, but if you make the right choices, you implement the right mindsets, and I don’t, you might end up being a happier person than I am.

[00:31:41] So in a sense, it’s the perfect half full, half empty story, which is, yes, it is absolutely unequivocal that our genes matter in how we perceive the world and how dispositionally happy we are, but that doesn’t mean that we are fatalistically doomed to that biological imperative. We can still alter it.

[00:32:02] Now, to your point about when you’re pushed into the lake, what do you attribute it to, there’s an interesting psychometric scale that was developed in the 60s that maybe some of your listeners are familiar with. It’s Rotter, R-O-T-T-E-R. That’s the name of the gentleman who developed the scale.

[00:32:20] It’s called internal versus external Locus of Control, which I’m sure you’re familiar with. Internal locus of control is I attribute things that happen in my life to me. So I did really well on the exam because I studied hard, and I’m smart. On the other hand, external locus of control, you attribute it to outside. It’s destiny. It’s God. It’s the environment. So I did poorly on the exam because Professor Saad is an asshole who doesn’t know how to teach.

[00:32:51] Now, the reason why I gave those specific examples, because to the point about happiness, most people tend to attribute successes internally and failures externally. And the only people, by the way, Dave, who don’t succumb to that rosy attributional style are clinically depressed people, which then begs the question– it’s a chicken and egg question– is it that they started off innately being less rosy, more accurate in their attributional styles, which made them more likely to develop clinical depression, or is it the clinical depression that then makes them less likely to succumb to the rosy attributional style? And the research is not clear, but like most things, it’s a bit of both.

[00:33:38] Dave: Okay, it makes a lot of sense it’s a bit of both. Um, I would say, I was a pretty, angry, and anxious, uh, person when I was younger, but I didn’t necessarily even recognize it. I just thought that’s how everyone was. It didn’t seem different from the norm. And over time, I acquired the skills, and went to Nepal and Tibet, and learned meditation from the masters and different lineages, and did all this weird stuff and got to the point where I can take responsibility without feeling like I’m going to die.

[00:34:09] And I understand too that it’s a great evolutionary strategy to not do that because if you were to build human hardware as if our conscious brain wasn’t in there, and your body doesn’t really like it that you’re in there as far as I can tell, um, and then you follow a set of behaviors that guarantee survival of the species, which is, run away from scary things or kill them, don’t think about it.

[00:34:32] Do it before you think about it, then eat everything before you think about it, then fuck everything else before you think about it to make sure that there’s another species. And if there’s anything left over, go build a community or whatever. They’re mercenary, but it feels like that’s how our hardware works, and it’s our job to overcome that. Does that model jive with what you’ve learned?

[00:34:51] Gad: Yeah, so I’ll attack the evolutionary angle from a few places. So in the book, I talk about the mismatch hypothesis, which I’ll explain in a second, as an impediment to happiness. The mismatch hypothesis originally came out of evolutionary medicine, and it basically argues that many traits, or preferences, or behavioral patterns that would have been selected because they were adaptive in our ancestral environment become maladaptive in the contemporary environment if the contemporary environment is different from the environment in which that trait evolved.

[00:35:28] Let’s take a classic example, our gustatory preferences. So most of us have gustatory preferences, whereby we’re attracted to some form of high-caloric food. Now, there might be individual differences. I may like chocolate mousse. You may like a juicy steak, but we probably both like these two food sources.

[00:35:48] So the mismatch hypothesis basically is, in today’s environment where we there is no caloric uncertainty, where there is no caloric scarcity, then that preference for high-caloric food creates a mismatch. And therefore, colon cancer, and heart disease, and diabetes, and high blood pressure.

[00:36:08] So if you look at, I think the top eight or nine killers, many of them are attributed to this mismatch hypothesis. That mismatch hypothesis also applies to our happiness in social settings, the idea being that we’ve evolved to be in groups, what Dunbar called Dunbar’s number of 150. We’ve evolved in small groups precisely because we’re able to then computationally maintain these reciprocal arrangements with a small band of 150 people.

[00:36:35] I scratch your back. You scratch mine. Uh, I scratched Dave’s back, but he never scratched mine. He seems to be untrustworthy. I should stay away from him. Beyond 150 people, it becomes difficult for most brains to keep track computationally of all these relationships. So the maximal optimal groups have typically been around 150.

[00:36:54] Now, imagine in today’s urban environment where I may live in Manhattan in front of eight million other people, but I’m actually alone in the sea of humanity because I haven’t replicated this tight bonding of small social ecosystems that my brain and yours expect. So the first evolutionary argument I would make is that people are generally happy if they don’t have this mismatch hypothesis being operative.

[00:37:22] So if I can live in an environment where I have to walk for my food, assuming that I can, where I don’t gorge on high-caloric foods, where I have meaningful relationships with a few people, then that’s going to, on average, make me happier than if I don’t, number one.

[00:37:38] Number two, also relating to this evolutionary framework, many adaptive traits become maladaptive when they misfire. So take, for example, OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder. The evolutionary route for OCD is that the idea of scanning the environment for environmental threats makes perfect adaptive sense.

[00:38:02] The problem is that OCD is a hyperactive firing of this otherwise adaptive process. So let’s suppose I say I want to check that the oven is closed. Okay, so the warning flag goes up, I check that the oven is closed, warning flag goes down, and then I go on with the rest of my day. The OCD sufferer has a hyperactive flag whereby they are now stuck in an eight-hour infinite loop of checking the oven.

[00:38:32] And so the adaptive mechanism becomes maladaptive when it becomes hyperactive. And so there are many different evolutionary angles that we can tackle to try to understand why we’re happy, and in some cases, why we become miserable.

[00:38:47] Dave: So beautifully said. All right. If you and Jordan Peterson arm wrestled, who would win?

[00:38:57] Gad: Here’s what I could tell you. If it was a game of who’s taller, he wins. Arm wrestle, I think I’m more– mesomorphic body type, shorter, more compact, lower center of gravity. I’d like to think that I’ve got more explosive power, but who knows?

[00:39:15] Dave: I’m pretty sure that if we set you guys up to arm wrestle in the Roman Colosseum, you would pull in almost as many people as Elon and Mark Zuckerberg.

[00:39:25] Gad: Thank you. That’s a very kind– we will be in a Colosseum, although a friendly Colosseum, next week, where we’ll both be speaking at the Budapest Demography Summit where we’ll be talking about this very corrosive and dangerous idea, families matter.

[00:39:44] Dave: I’m sorry, we’re going to have to end the interview on that. How dare you have an independent thought, whether it’s right or wrong? Families do matter. And as a father of two thriving teenagers, uh, anyone who’s a parent and thinks families don’t matter probably didn’t experience one. And if you didn’t have one, you can replace it with all the psychological stuff. You can do some healing, by the way.

[00:40:09] Gad: Just let me give you a quick story about happiness and having children. You’re ready?

[00:40:14] Dave: Yeah.

[00:40:14] Gad: So I receive all kinds of lovely emails from all sorts of people. Some can be fancy professors. Others can be a corrections officer or a truck driver. All of these mean a lot to me, and it’s wonderful that people love your work, but you know what’s the most wonderful? When I walk off a podium, uh, at a major event where my family is there, and my teenage daughter– the reason why I mention teenage, because as you know, there’s a developmental stage where you go from being the hero to a zero in your teenage children’s lives.

[00:40:44] Dave: That’s an evolutionary adaptation because of Dunbar’s number.

[00:40:49] Gad: Exactly. And so when your daughter comes up to you, hugs you, as she did in my case, at the end of my talk, and said, daddy, I’m so proud of you, I love you, that’s what happiness is.

[00:41:02] Dave: That’s a beautiful, beautiful tale. And yeah, it is. Uh, when your teenagers say they love you, you know you did something right because evolutionarily– I’ve been telling my kids this since they were five. Guys, we evolved to be in tribes of 150 people. And what would happen, when you hit your fertile years, when you enter puberty, if you didn’t decide that your parents and relatives were the dumbest creatures on earth, you would probably try to mate with them.

[00:41:30] And then within three generations, we would all be basically retarded or whatever the politically correct word is for when you have the wrong genes and all that stuff and things are scrambling. So then Mother Nature has configured you so that you’re willing to risk dying of lions, tigers, and bears to find the next tribe where there aren’t dumb people. And when you’re 24, magically, will be smart again. And that’s okay. And I love you anyway. But it is because of evolution that I’m going to be dumb for a while.

[00:42:00] Gad: Beautifully said. But I would argue, by the way, that it also works the other way. You just described it as to why they wish to detach. Let me do it the other way. And I actually did a Saad Truth clip that’s, uh, on my channel that speaks to this. So in Arabic, in Jewish Arabic– we’re Lebanese Jews, so my mother tongue is Arabic, but there is some Jewish words that seep into Arabic.

[00:42:25] So there’s this expression, which I’ll say it in the language, and then I’ll translate it. It’s sin el shalut, which means basically, if you translate it, the age of obnoxiousness. So whenever, let’s say, you see a teenager and you go, oh my goodness, you’ve entered sin el shalut, that means, my God, are you obnoxious?

[00:42:44] And so I argued, speculatively, but I think quite plausibly, that nature has also endowed us with this ability to find our teenage children to be so obnoxious that we want to decouple from them. So I’ve recently told my wife, you know what– and I can’t believe I’m saying this because I’m very much of a family man. I really am a father hen kind of guy. I said, I think I’m ready to go on vacation without our children, love, because I’m finding them so unbelievably obnoxious these days. So I think it works both ways.

[00:43:18] Dave: I never thought of it, but it absolutely does because I may or may not have had a conversation like, can we sell them on eBay or not? Yeah. All parents get frustrated, but it makes so much sense because Mother Nature doesn’t want us to mix our genes in the wrong way. It’s not like she’s going to rely on us to think about it that way, because our thoughts are all muddled stuff.

[00:43:38] It’s going to be a biological imperative that feels true, so we’re going to believe it’s true. And it’s that feeling true thing, in my work anyway, that’s the source of intuition and just an inner knowingness. It’s also the source of your ego getting in there and taking control of your behaviors and making you into, I don’t know, a vegan radical who cancels people who eat the most sustainable food on earth, which is cows. Oh, sorry. I just had to put that in there in case there was any of them listening.

[00:44:05] Now, I want to go back to what you said in your book, that there are two key life decisions that matter most for happiness, the right life partner and the ideal job. So is that the same at all stages of life? So I’m single right now, and I’m truly wondering whether I really want a life partner because I’ve already done that for 17 years. So is this true at all ages?

[00:44:31] Gad: Yeah, great question. So for some traits, yes. For some traits, no. So example, the cheerleader who’s looking for a particular set of physical attributes in her ideal partner for homecoming queen wants the tall quarterback, that becomes incredibly less important when she’s 32, a neurosurgeon resident, and it might no longer be relevant because that quarterback, even though he remained tall, he’s now fat, never finished his high school degree, can’t put two words together, and the exact guy that she used to fantasize about when she was 17 would be the last guy she would want.

[00:45:17] So there are some mating attributes that will vary in their importance across the life cycle, exactly to your point. What I think doesn’t change is the following. When I discuss the choosing the right spouse as a key pathway to happiness, I pit two evolutionary maxims against one another. There is the, what’s called opposites attract maxim, versus the birds of a feather flock together maxim.

[00:45:46] Now, you might say, well, birds of a feather flocking on which feather? It’s not so much on your eye color should be the same or your hair color. It’s that you should share the fundamental same belief system, grand attitudes towards life, key mindsets of how to tackle life. If I am a caustic atheist and everything you do is grounded in your faith, it’s not going to take a fancy evolutionary psychologist to realize that that’s starting us on the wrong foot, notwithstanding that we might have many other compatibilities.

[00:46:18] So it turns out the research shows, Dave, that overwhelmingly, if what you’re interested is in the long term success of your union, it’s very much birds of a feather flock together that’s operative. On the other hand, for short term mating, I’m just looking to have a one-time dalliance behind the bushes, then opposites attract might indeed be very titillating because it’s a one-time deal. I might be sexually restrained and introverted. You may be the exact opposite. You bring me out of my shell. We have a great encounter. But for long term union, birds of a feather flock together.

[00:46:52] Dave: Got it. So you want someone who’s similar to you. Okay, so someone who’s past or at least wanting children age because you’ve already had them, like where I am. So is having a life partner as important or necessary, even if they have the same feathers, in your 50s, 60s, 70s, versus having multiple partners, or having a close group of friends, or serial monogamy? There’s all sorts of things people are doing these days, but I’m just wondering.

[00:47:22] Gad: I think that what you just asked might apply across all life stages for the following reason. We truly face a conundrum as a sexually reproducing species. And that’s why in one of the later chapters of the book, I talk about the virtues of variety seeking, but then I put in brackets sometimes because I discussed the pursuit of variety in many domains, food variety seeking, exercise variety seeking, intellectual variety seeking, and sexual variety seeking.

[00:47:51] While sexual variety seeking has clear evolutionary roots, but also, if you’re in a monogamous union, it could pose problems. So let me discuss these two opposing tugs. On the one hand, it is incontestable that both men and women have evolved a desire for sexual variety seeking.

[00:48:10]

[00:48:10] Dave: People who don’t believe that are just repressing the fact that they saw someone attractive and were not shamed over that.

[00:48:17] Gad: What is also incontestable is that across all cultures, it’s an absolute human universal, men have a greater penchant for sexual variety seeking than women. That doesn’t mean that women don’t have that variety seeking penchant as well. And I’ve built, if you’d like, the nomological network that demonstrates that women also have a deep desire for sexual variety seeking. And there are very clear evolutionary reasons why we would be interested in sexual variety.

[00:48:49] On the other hand, there are also very clear evolutionary reasons why we would have a deep desire for long-term pair coupling, because we are a by-parental species, officially, biologically, compared to other mammalian species. Human dads are truly super dads. We do a lot more than just provide a seed.

[00:49:15] In many mammalian species, there’s the copulation, and that’s the only contribution of the male. We are truly super dads in the animal kingdom. Plus, we have a long period of offspring juvenility, meaning that it takes many, many years before our children enter the sexually reproductive stage, where, as we talked earlier, they want to break free from you.

[00:49:37] And therefore, it makes perfect evolutionary sense for us to have evolved the hormonal markers, the neuroanatomical systems to feel romantic love. I truly am nonstop obsessing over the singular woman. I only want to be with her. But then six, seven, eight, 10 years into that relationship, here comes this other woman.

[00:50:00] It doesn’t stop the fact that I love my wife. Boy, I’d love to have an encounter with her. I can’t give the prescription of what each individual should do, but what I can absolutely confirm is that it is perfectly natural that we feel that conundrum because both these evolutionary drives are pulling us in opposite directions.

[00:50:21] Dave: I think Chapter 4 in your book says all good things in moderation. So I think you just did write a prescription there.

[00:50:28] Gad: Yeah, although for most men, their moderation would be, I’ll sleep with 10 other women other than you, sweetie. But of course, in your case, you only sleep with me. That’s the moderation. Because as we know, men face paternity uncertainty. Women don’t face maternity uncertainty. That’s why we’ve evolved the cognitive, the behavioral, and the emotional system to really be triggered by threats of infidelity from our women.

[00:50:56] Dave: One of the things I like to say at the start of my public talks is that if anything I say triggers you, it means you’re walking around with a loaded gun, and you might want to unload that. Because if you can be triggered, you need to grow up. You need to get a therapist. So in my case, I guess I never cheated on any relationship because my word and my integrity really matter, but like all human beings, I’ve often thought, wouldn’t that be fun?

[00:51:24] Gad: That’s lovely. First of all, I highly respect you for that. And I can say right here that I too have not cheated. And I think what I’m about to describe for myself, based on what you just said, could probably apply to you. People ask me, why do you fight the battles that you fight? You already lead a very stressful life as a professor with a research lab, so why do you get engaged in all these kinds of things?

[00:51:50] And I usually tell them, and the answer I’m going to give also applies to cheating on your partner, say, I have a very exacting code of personal conduct. I’m my worst critic, meaning that when I go to bed at night and put my head on the pillow, I won’t be able to sleep at night if I feel that I was in any way inauthentic because then I would feel as though I’m a charlatan and fraud.

[00:52:12] Therefore, if I walk away from an opportunity to defend the truth, that means I wasn’t fully honest at that moment, and therefore, I just can’t walk away from those fights because– in the same way that, if you see someone being mugged, you could be one of two people, you either intervene, or you pretend you didn’t hear the screaming. And so I think it’s the same thing for cheating.

[00:52:35] My wife once told me, I think jokingly, but maybe not, she said, you know what, if you cheat on me, that’s okay if I never find out. And then I said to her, but I would find out. I would know. So thank you for giving me that green light, but guess what, you must have married the right guy because it doesn’t matter to me that you would give me the green light. I wouldn’t give myself the green light.

[00:52:58] Dave: There’s some cultural variety there, though. In the US, that’s absolutely not, but if you go to France, mistresses are pretty common. I traveled around China a good amount earlier in life, and I go out for drinks with guys who are married, happily married, and, oh yeah, let’s go to the other club. And like, that’s not my kind of club.

[00:53:21] But there’s, oh yeah, I have a girlfriend. I pay for her apartment. I’m like, that’s just normal. Everyone does. So it could be, and I’ve talked to some Asian friends, who are married, saying, yeah, that’s how it is. And I knew about that, the wives. I knew about that. It’s part of our culture. And they’ve actually said that to me. I’m not saying it’s part of all culture from any part of Asia, but it was interesting where there’s an acceptance of that side of things that varies by how you’re raised. So maybe she was curious.

[00:53:52] Gad: Yeah. So what you just said is actually a very, very important evolutionary point. So let me first describe it broadly, and then I’ll link it to the cheating story that we’re talking about. So there’s a subfield within the evolutionary behavioral sciences called behavioral ecology. Behavioral ecology is the field whereby you study cross-cultural differences via the evolutionary lens.

[00:54:18] Meaning, your example of why culture A tolerates polygyny more than culture B itself is an evolutionary adaptation. So let me explain in another concrete example. If you look at international cuisines, you will notice that some are much spicier than others. Mexican food is spicier than Swedish food.

[00:54:43] Now, if I were a cultural anthropologist, I would simply revel at having discovered that difference. I will publish a paper saying, hey, I went to the Yucatan and there is more spicy food there than there is in Stockholm or Gothenburg. And the paper would end there. Mic drop. The evolutionary psychologists or behavioral ecologists would come along and say, wait a second, is there a biological explanation that can explain the cross-cultural differences in spice use?

[00:55:16] And it turns out that there absolutely is. Cultures that are located in places that have higher ambient temperatures are more likely to use spices in their cuisines because cultures that have higher temperatures, there is greater, uh, pathogenic load foodborne pathogens that will proliferate more quickly with heat. Therefore, the use of spices becomes an antimicrobial adaptation.

[00:55:48] So the cultural adaptation of using spices or not using spices is itself a biological adaptation. So now I’m going to link it back to our earlier question that some cultures tolerate women on the side more than other cultures does not speak to the vagaries of culture that itself is due to evolutionary reasons. And this is why when people understand the explanatory power of evolutionary psychology, they truly have an epiphany, because there is no other game in town. You can’t explain human phenomena without drawing on evolutionary theory.

[00:56:28] Dave: That’s profound. I think between evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology, you can explain almost everything that people do. One of the evolutionary biology things that I talked about on the show, and as far as I know, this is the first time that it’s been talked about. I didn’t find any papers on it, but it’s one of those things where you know it ought to be true because everything lines up.

[00:56:53] Birth control pills are hormonal things that disrupt pheromones. And we know that when men are not around pheromones, notice if we can’t smell fertile women in our environment, our testosterone drops. And if you want to look at the epidemic of guys living in their mother’s basement playing video games till they’re 30, 85% of women are wrecking their biology with chemical, industrial birth control that helps them be better worker bees, but maybe goes against the face of biology. So I’m a big fan of birth control, just hormonal birth control is a crime against women. It’s also a crime against men because we need juicy women around us so we give a crap about life.

[00:57:34] Gad: Wow, there’s so much good stuff there. So let me take it in several places. Number one, there was a study that was done by a good friend of mine, fellow evolution psychologist, Geoffrey Miller. I’m not sure if he’s been on your show. He wrote a great book called The Mating Mind, and I remember we were at the Human Behavior and Evolution conference together, and he said, hey, Gad, I want to tell you about a study that I’m just finishing, and we’re writing up, or something to that effect.

[00:57:59] And this is one of those cases where you meet a fellow scientist and he beat you to the finish line of a study that you were also going to do. So the story that I’m about to tell you is exactly one of those stories. So he had done a study, and you’re going to see why it relates to what you were talking about, showing– watch this. This is one of those mind-blowing studies. That strippers, exotic dancers receive a differential tip amount depending on where they are in their ovulatory cycle.

[00:58:32] When they are in the maximally fertile phase of their ovulatory cycle, they receive much larger tips than when they are in the luteal phase, in the non-fertile phase. And so to your point, there are two reasons that that could be happening, and I don’t think he teased out which of the two it was.

[00:58:49] Number one, it could well be that when women are maximally fertile, they feel sexier, therefore they engage in more showy behavior. They dance in a more provocative way. They are more lascivious in their movement, and therefore that attracts patrons who pay more for you. And/or it could be, to your point, that men have evolved the capacity to detect which we used to call cryptic cues of ovulation, but they’re not so cryptic because we know, for example, that your breast symmetry in a woman becomes more symmetric when you are maximally fertile, and we’re attracted to symmetry.

[00:59:28] We know that your skin is more intoxicating visually when you are maximally fertile. We know that your smell is different and more attractive when you’re maximally fertile. So it could both be that the women are dancing in a more sexually attractive way, and the patrons are picking that up and therefore show that by paying her greater tips, to your point.

[00:59:50] Dave: There’s another study, and this is politically incorrect, but it is a study that shows that less intelligent women become smarter during ovulation, and more intelligent women become dumber during ovulation.

[01:00:03]

[01:00:03] Gad: I’m sure I could find it, but please send me the link to that paper. I love that.

[01:00:08] Dave: I will look for it. It’s actually one I heard about from my former wife. We talked about it at length, but I know it’s in my records somewhere. What I’ve also recommended, uh, because I’m an advisor and investor in a lot of companies, and I don’t think it’s unfair if you’re a woman and you’re not on the pill and you’re raising venture capital and you happen to pitch when you’re ovulating. I’m sorry, I would take full advantage of my biology. You are much more likely to get that check for reasons that are entirely invisible to our conscious minds because there was something about you that was really interesting, and they wanted to write the check, and there was nothing wrong with that.

[01:00:46] Gad: By the way, you just literally describe– I’m assuming that that study hasn’t been done. I’ll start my teaching later this week for the semester, and in all my courses, irrespective of whether I’m teaching at the undergraduate, MBA, MSC, PhD, I always make students do this semester-long research project where they have to identify a research question, posit hypotheses, develop the data collection instrument, collect the data.

[01:01:16] Literally go through the whole process. That’s mind-blowing for them because it’s the first time they’ve ever done that. Let’s suppose you were in my class. You just propose the research question. Does the ovulatory cycle affect proclivity of receiving venture capital funding? And look, it’s very clean. I always tell my students, if a research question cannot be explained to a 10-year-old, that means it’s too muddled.

[01:01:43] Now, short of the fact that maybe a 10-year-old doesn’t know what ovulatory cycle is, the relationship is very clear. You’re basically hypothesizing, when the woman is maximally fertile, she’s more likely to unlock that wallet of the venture capitalists. By the way, I bet you now someone’s going to listen to our chat, steal this idea, and do a doctoral dissertation on this project based on your idea, Dave.

[01:02:06] Dave: It wouldn’t be the first time from this show. Ideas are cheap, studies are hard. So if you choose to do that, thank you for doing it. And if you’re sitting here feeling, either as a man or woman, that that’s somehow unfair, this is the playing field that we’re in. And what’s not fair is that when the me-too movement started, many of my female entrepreneur friends were just pissed because they’re saying, I can’t get a meeting with VCs because they won’t take a meeting alone because then there could be an accusation.

[01:02:34] So there was a big backlash there that wasn’t fair because it’s already harder for female founders to raise money, then all of a sudden, they can’t get meetings because there’s this societal movement around trying people without a trial, uh, and crucifying them. So a lot of the VCs really reacted with fear out of this.

[01:02:52] So if that helps to balance things out, that’s fine. And I’ll just say straight up, a guy who isn’t polluted with plastics and basically things that disrupt estrogen, if you’re aware of your senses, you can identify women who are ovulating. Maybe not with 100% hit rate, but probably an 80% hit rate if you’re in the same room with them and paying attention because there’s something different about them. And you can correlate after a while, oh, that difference is that. And this isn’t about sexual attraction or attention at all. It’s that there’s something different about them.

[01:03:26] Gad: I’ve actually had this happen with me with my wife several times where we joke around where some woman passes by, she looks disheveled and in sweatpants, and I will turn to my wife, and she goes, yeah, yeah, I know. She’s not ovulating. And then when I see another woman and she’s doing the stiletto walk, I say, oh boy, somebody is ovulating today.

[01:03:48] And of course, I haven’t empirically tested it. Actually, I have empirically tested it, not in the context of our anecdotal lives, but I did a study with one of my former doctoral students where we looked at the effects of the menstrual cycle on beautification practices of women. And not surprisingly, we found that when women are in the maximally fertile phase of their menstrual cycles, they beautify more.

[01:04:11] Now, beautification could be stilettos, it could be wearing the hair down, it could be putting on more makeup, it could be more scantily clad. There are many ways by which a woman can beautify, and she’s much more likely to do it when she is maximally fertile. That’s the power of evolutionary psychology.

[01:04:27] Dave: I’m curious what men do, because John Gray, the Mars and Venus guy, is a friend, and we’ve had lots of conversations about how after mating, men’s testosterone drops precipitously for 24 to 48 hours. In fact, that’s why I’m a fan of semen retention much of the time. There’s equations I’ve talked about published, ejaculation data in my books, and all kinds of stuff.

[01:04:49] Just saying this is a variable in your psychology that you need to be aware of, especially if you’re using porn. It’s going to make you depressed. And there’s a biochemical reason testosterone drops, which also drops dopamine, which means you’re not happy all the time, and you’re looking for the next fix. It’s a dark place to be. But even if you’re having sex all the time, there can be problems with it.

[01:05:08] So are there patterns in men you’ve picked up that are similar? For a woman, there’s a month-long period. We’re looking at about a five-day window. But for guys, we have a monthly cycle, but it’s very subtle. So what can we do as men or as women looking at working with men to look at the evolutionary effects of our mating behaviors?

[01:05:26] Gad: Yeah, that’s a great question. So I haven’t done any studies looking at specifically the relation between hormones and ejaculation, but what I’ve done in the case of men– so I just described a study with ovulatory cycle and women’s beautification. In the men’s case, I’ve done a study with another one of my former graduate students where we looked at testosterone, so to your point, to your question, and the use of conspicuous consumption as a strategy.

[01:05:55] So conspicuous consumption is showy behavior via the use of products. And so we did a study, and both of these papers are published in really, if I may say, truly prestigious journals. And I can send you the links if people want to look them up. I did two studies with this other student linking testosterone and men’s behaviors. I’ll mention the first study for now.

[01:06:22] We actually rented a Porsche. This is not, imagine you’re driving a Porsche and then you do the experiment in the lab as most psychology experiments. We actually rented a Porsche. And I always tell people, what was the most impressive part of that study is trying to get a granting agency to give you money so that you could rent a Porsche for science.

[01:06:45] Now, that’s impressive. So we had young men come to the lab where we had them drive both– so this is called the within-subjects design. They both drove the Porsche and a beaten up old whatever, uh, car. And we did it in two environments. They drove both of those cars in what’s called the Lek. L-E-K is a zoological term where you go to engage in sexual signaling. You see it in many other species, let’s say bird species.

[01:07:18] The males come in, start ruffling their feathers, the females sit around the periphery, and then they pick the top dog. Well, in the human context, a lek would be downtown Montreal on a weekend where everybody congregates, and therefore all the young men come around in their fancy cars. So we asked them to drive the car, both in downtown Montreal and on a semi-deserted highway.

[01:07:39] Basically, in one case, there’s an audience, and the other case, there is no audience. And what was the dependent measure here? We took salivary assays so that we could then measure their fluctuating levels of testosterone. So we first had a baseline measure, then we had the four measures of the four experimental conditions, and then we took another baseline measure.

[01:08:02] And not surprising to probably anyone listening to the show– I’ll just mention one of the findings– when you put young men in a Porsche, their testosterone levels explode. Now, what’s the reason for that? And by the way, one reviewer, when we were going through the peer review process, said, how do you know that that’s just not because they’re driving fast and so on?

[01:08:25] Number one, we gave them very, very strict, uh, instructions not to do that. But number two, when they are driving around the block in downtown Montreal, it’s like driving in a parking lot. It’s bumper to bumper, so you can’t even instantiate the speeding stuff. So it can’t be that. We’ve ruled that out.

[01:08:43] The reason is simple. We know from many animal studies and human studies, when two same sex rivals fight with one another, the winner has a rise in testosterone. The loser has a drop in testosterone. So once I imbue you with a high social status symbol, like the Porsche, you’re a winner, your tail goes up, endocrinologically, your testosterone goes up. So that’s the kind of studies that I’ve done in my lab.

[01:09:08] Dave: That is so fascinating. You’re reminding me I should put on a watch. So I’ll put on my fancy watch. So if you guys are watching, this is a two-pound laser watch that would actually repel women, much like my toe shoes. It’s a male birth control watch. These are real things.

[01:09:26] And what you’ve also done is allowed high-end concierge physicians to write a prescription for a Porsche, which makes it tax deductible to raise testosterone. I’m not even kidding. If you have a doctor that will write that, this should pass. Also, your insurance won’t pay for it, but you can deduct it as a medical cost.

[01:09:43] Gad: I’ve made the exact same joke to my wife. I said, look, if I ever start slowing down in the bedroom, it’s science that I have to buy a Maserati. And you have to go with that because if you want me to keep up in the bedroom, that’s just a medical situation.

[01:09:58] Dave: Did you just justify the midlife crisis? It’s actually a drop in testosterone that’s cured by a sports car. I think you did.

[01:10:05] Gad: I think I did. And I think I deserve a Nobel prize for that.

[01:10:08] Dave: Uh, two. Absolutely. Only one guy’s ever won two, but you could be the second guy.

[01:10:12] Gad: Linus Pauling.

[01:10:14] Dave: Hey, you know who it is. That’s amazing. Um, it’s a little story. Years ago, when I was 300 pounds and really sick, I went to my doctor in Palo Alto and said, I feel like I’ve been poisoned. Something’s wrong with me, uh, but vitamin C seems to help. And he goes, how much do you take? And I said, three grams a day. And he goes, stop, it could kill you. And I said, what about Linus Pauling? And he said, who? And I said, you’re fired. It was on–

[01:10:35] Gad: If your physician doesn’t know Linus Pauling, he’s not good. Or she.

[01:10:40] Dave: And if you’re listening and don’t know who Linus Pauling is, two Nobel prizes, took 90 grams of vitamin C a day. But I will tell you, given what I know now, I don’t recommend you do that for something called oxalate, especially if you’re vegan and you do a lot of spinach and crap, like I did when I was vegan, because vitamin C plus spinach, and kale, and almonds, and sweet potatoes equals really, really bad problems. Different podcast episode, but nonetheless.

[01:11:04] All right, you have some other interesting stuff, uh, that’s in your book. You have time for another couple questions?

[01:11:11] Gad: Let’s do it.

[01:11:12] Dave: Earlier on, I mentioned Burning Man, and Chapter 5 in your book about happiness is life is a playground. And I try to explain to people, I go to Burning Man because it’s adult play. You’re doing stupid stuff. I wear ridiculously short shorts. People are like, are you gay? I’m like, no, I’m not gay. I just think it’s funny that I can walk around saying, excuse me, my eyes are up here. It’s a shtick. It’s a joke.

[01:11:36] And people get so offended who aren’t at the burn. Everyone at the burn just laughs. But to me, that’s play, and it’s just like yanking people’s chains, and you just ride bikes around and do stupid stuff. But it’s so, I don’t know, it just creates happiness, and I can’t tell you why. So what does playfulness mean in your context? I’m assuming it’s not Burning Man.

[01:11:55] Gad: Love that question. So again, sticking with the theme of evolution, there are amazing evolutionary psychologists that have studied why play is adaptive. Now, you can study it in other species, or you could study it in the human context, and the general story is the same from an evolutionary perspective.

[01:12:15] And that is that play allows us to instantiate, at the developmental stage, certain behavioral patterns that later in life will be adaptive. So for example, if you’re a prey or predator species, when you are a juvenile, you will play. You will pretend that you’re a prey or a predator. You will wrestle with each other precisely because a lot of these motor skills, a lot of these behavioral patterns will prove to be adaptive later.

[01:12:44] Now, that might imply that you grow out of play. So yes, it is important to play when you are young, but then adulthood is too serious to play. And of course, as you showed with Burning Man, that’s not true. So in the context of my book, I argue that even in the most dire and serious situations, play is an indelible part of human nature.

[01:13:07] And I’ll just mention maybe two or three quick examples. Number one, as an academic, you would think, okay, science is serious business. No, science is the ultimate form of play. Because what am I doing as a scientist? It’s puzzle making. There’s a bunch of variables that are floating around, some of which are unrelated to one another, others that cause others, and my job is to try to make sense of all of these variables floating in the sky.

[01:13:38] Isn’t that what you’re doing when you’re solving a 1,000-piece puzzle with your child? You are trying to solve a puzzle. And by the way, I’m not the first one to argue that, and I give several really cool quotes in the book, of other, in some cases, well-known scientists who’ve argued that the reason why they’ve been successful as scientists is because they view it as a form of play. And I so relate to that. That’s what gives me existential glee. Because science, if practiced properly, is nothing but play.

[01:14:09] But let’s take a more dire situation. I grew up as a child of the Lebanese Civil War, and usually, most wars are judged against the backdrop of the brutality of the Lebanese Civil War. That was some brutal house-to-house death fighting. It was unbelievable. Death awaited you at every corner.

[01:14:28] And even in the context of such a dire situation, I would still find time to go out and play, and my parents would tell me, and I mentioned this exact story in the book, they’d say, if you’re going to go out, don’t pass this particular line, imaginary line, because that then opens you up to the eyesight of the snipers who will then blow your brain.